My head has been a flurry this past week. Headlines detailing the executive order to keep meat packing sites open, the disproportionate effects of COVID-19 on black and brown individuals, and Navajo Nation now third in deaths across the entire U.S., trailing New York and New Jersey. It’s a really easy hole to get sucked into, and be left with the question, “What does activism in the time of social distancing look like?” Access to health care is limited, movement forward is unclear, and testing is still limited.

Today, as I write this, it’s May Day: a celebration of spring also deemed International Day for Workers. This May Day came with virtual celebrations for many organizations and mass protests. We see picket lines forming and demands being made. Workers in essential positions are raising the questions:

- What does it mean to be “essential” right now?

- Why are the needs of so many “essential workers” remaining unaddressed?

The reality can be deeply discussed, and a matter of Marxist Feminism holds some pretty critical answers, but I remain hesitant to turn this into an academic paper, so I will continue.

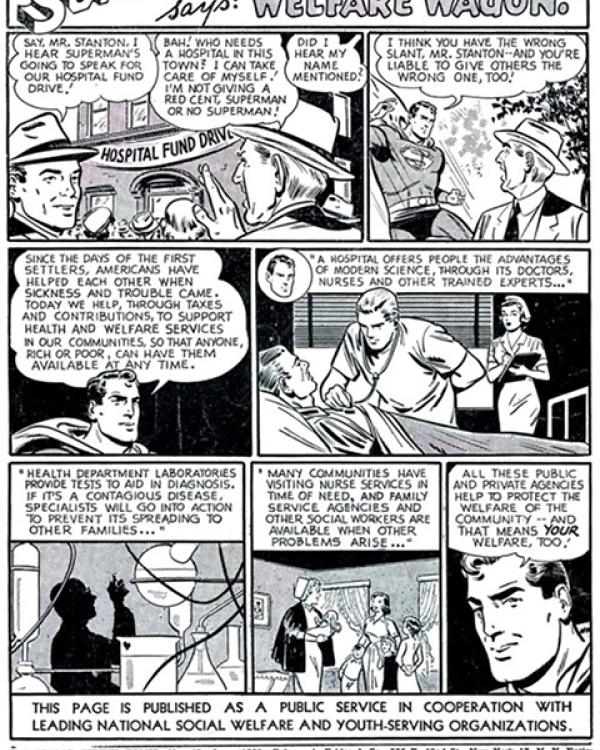

With some of my friends working “essential jobs” and being thanked for their heroism, I flash upon a myriad of memories that any hero would prefer to remain private and fail to see their cape. Yes, I love them, and I am proud of them; they make positive impacts on the lives of people. But really, they’re going to work because they have rent to pay, and their job gives them a paycheck. The way the larger society classifies what jobs are important has changed with COVID-19, but the rhetoric around essential workers has situated their work as morally admirable rather than an economic necessity for the continuation of the nation. What I mean (my writing gets away from me) is that we call essential workers “heroes” but I know for a fact Bruce Wayne AKA Batman was not living below the poverty line and unable to pay rent. Actually, Superman was pro social welfare in the 50s, but as our image of what it means to be a hero has changed to individualism and personal morality, Superman suddenly stopped proposing welfare for all. Our changed understanding has left the needs of “essential workers” and “heroes” unaddressed. I find myself putting my head in my hands, trying to comprehend the rhetoric of “grocery workers are heroes” when we fail to provide health care services for those who provide our food access. How can you be a hero to someone if you don’t have a means of living?

From early April, a headline from Washington Monthly poignantly puts it, “The Irony of Being Essential but Illegal.” If not obvious, the irony is much of the national rhetoric labels undocumented immigrants as “illegal,” but now without those “illegals” we couldn’t feed our society. Trump announced that meat packing plants would remain open. With the number of COIVD-19 cases rising, I’m left to wonder how one could possibly ignore close working conditions in a debatably necessary environment. Yet, the need for a paycheck remains, as well as an economic reliance on the production of food. The same goes for agricultural laborers. But, we’re not talking about lack of access to health care for most if not all of the workers providing the food that appears in the aisles of the grocery store. By all means, this is not to paint a helpless picture, as no one needs my white tears. Undocumented workers are as involved as other “essential workers” in current protest. Rather, it is my question, that from a place of privilege, what does support look like for correcting the present injustices in the face of a pandemic? In the ivory tower of academia, the relevancy of my work seems far removed from the direct needs of our essential working force at this moment. Like I said, my head has been a flurry this week.

Happy May Day, GGSE. Remember the working class that maintain the small semblance of normalcy that can be experienced in a place of privilege. If you are able, don’t cross the picket line.

Mary Franitza is a first year MA/PhD student in the Department of Education. She started her quarantine with a frantic two-day road trip from Santa Barbara to a small coastal corner of Wisconsin. Mary is spending her time social distancing with her adult family members, two parents (sixty-four), and sister (thirty) and her just as adult cats, Dodger (soon to be ten) and Socrates (probably thirteen). Whilst at home, Mary is still responsible for work with high school seniors at Santa Barbara High School and tending to her course load and research. Mary is approaching quarantine with a critical feminist lens as she watches the pandemic unfold in her hometown.